How the current political stalemate in Israel affects domestic, regional and global security issues.

On September 17, 2019 at 10:00pm, Israelis were watching the initiate exit poll results of the legislative election. Alarm bells about the significance of this day have been set ringing as election day was looming. Incumbent Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, already in power for the past 10 years (in addition to 3 more years in the 1990s) and a leader who became a symbol of the Israeli stance on the international arena, saw it as a critical battle for his own personal political survival. Rivaling Benny Gantz, leader of the Blue and White party and Netanyahu’s former army chief of staff, as well as his senior partner Yair Lapid, a secularist politician and once Netanyahu’s treasury minister, saw it as a golden opportunity to replace the ruling Likud party. All in all, 29 lists presented their candidacy, with 9 of them managing to secure enough votes to find themselves represented in the Knesset, the Israeli parliament.

However, the average Israeli voter, even the media, carelessly shrugged off the predictable election results, and were even happy to let the a particularly poisonous campaign’s dust settle, looking forward to a long holiday season while politicians were struggling to find a way out of the current political stalemate. As political commentator Amit Segal noted, “the people are divided as to the identity of the next prime minister, but united in their hope that may this year and its elections soon be over,” paraphrasing a New Year greeting.i

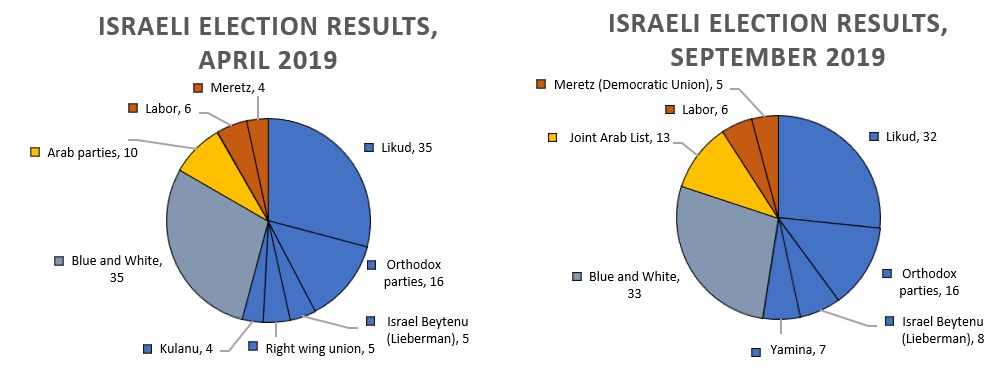

The circumstances this time were unusual, though. This was the first time since the foundation of Israel that a Knesset dissolves itself so shortly after being elected last April, and that a second round is forced upon the political system and the public. Then, Netanyahu was unable to form a majority due to the refusal of his once-partner Avigdor Lieberman and his party to join what they called a “Halakha government” or an “ultra-orthodox” one, in what the Likud saw as a political zig-zag in hope to garner more secular votes and aimed at toppling Netanyahu himself. Netanyahu chose to dissolve the Knesset rather than giving the mandate back to the President, who would have chosen another Knesset member to form a government instead.

Discouragingly and predictably, the results this time were not extremely different than the ones in April, which raised an immediate bafflement as to the need for another round. This time once again, no major party has secured a sufficiently large potential coalition, and now unclarity is dominating the political landscape. Voter turnout has been generally low since 2001 (69.4% in this election, a slight increase from April’s election 67.9%) and despite the relatively high interest Israelis have in politics (64%), almost 80% believe they have little or no influence on the government’s actions. Paradoxically, though, Israelis are generally satisfied with their lives, the country’s GDP growth is impressive and its GDP per capita has surpassed France, Japan and Italy, and compared to the past, the security situation is relatively stable. “The country is clearly on a roll,” wrote Stephen A. Cook in Foreign Policy. “Israel ranks as the 13th-happiest country in the world, its economy is steady at 4 percent unemployment, no one is afraid to board a bus, the tourists keep coming … The country can’t form a government, its peace process is permanently stalled – and things have never been better.”

Unlike in the US, UK, Canada and other democracies, in Israel there has always been a coalition based on several parties. Now Israeli voters are yearning to see stability after months of turmoil, and regional and world leaders are closely following the chain of events that will determine the direction in which Israel will be heading going forward. The current negotiations between the parties will determine the face of Israel in the near future.

The following is an analysis of the different scenarios as to the identity of Israel’s next government and the effect each of them can potentially have on domestic, regional and global security-related issues.

The Palestinians

A critical preliminary point is that even though politicians predictably marketize themselves and their parties as personally crucial to secure Israel’s near future, it is fair to say that many voters, as much as they acknowledge the set of values their vote represents, do not hold their expectations high from any form of a future government. To be more precise, they seem to care more about the prime minister’s identity than being able to articulate far-reaching differences between the two main parties’ agendas. Certainly, there are some core differences with regard to the religious-secular status quo or liberal market economy, but mostly the campaign focused on the Likud’s record with respect to issues like security, public transportation and hospital beds per capita vis-à-vis Blue and White’s capability as a new party with fresh politicians to execute them – and above all, on Netanyahu as a political leader. Ironically, the starkest differences are between the satellite parties – the Labor and the Democratic Union on the left, Yamina on the right.

Most importantly, this campaign has been a game of personalities. Netanyahu has positioned himself as “Israel’s savior”, and boasts his close personal relationship with world leaders as critical to its security – “a different league” in his campaign’s words. “I’m unimpressed by those who keep tweeting,” he mocked. “look what we did in recent years. Are they capable to handle Iran? Hamas? Trump? Putin?” Across the aisle, Gantz and Lapid have pointed at Netanyahu’s several corruption accusations, and boast the accumulate “117 years of security experience” of the top four party leaders, three of whom are former military chiefs of staff – the reason they are dubbed “the Generals’ party”.

The two campaigns relentlessly point out the alleged polar differences between them, but when facing tough strategic choices, usually reality and circumstances are stronger than any one leader or one government. One prominent example for that would be the policy towards the Palestinians, both in Judea and Samaria (“West Bank”) and in Gaza. The Netanyahu governments have been eliminating blockades to facilitate everyday life, allowing family visits from Gaza into Israeli prisons, authorizing and funding humanitarian aid with dozens of trucks entering and leaving Gaza daily, persuading the PLO to receive funds it refuses to take to keep its stability; the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories has been full cooperative with the Palestinian security forces and not one square centimeter has been annexed – all of that despite the militaristic rhetoric and the common impression in the international community regarding their policy, at times even dubbed “apartheid”. On the other hand, far-reaching offers by both Barak and Olmert governments at the negotiating table did not yield any results, and no one square centimeter has been evacuated and delivered to the Palestinians either. Hence, except for the Rabin government of the 1990s with the Oslo Accords, the only cases in which Israel evacuated territories or made major concessions towards the Palestinians have been ironically under right-wing governments, as was the case with the Sinai Peninsula, Hebron and the Gaza Strip.

Both main parties do not offer long-term conclusive visions in regard to the Palestinians, but rather vague short-term ways to manage the situation (starkly resembling one another); generally agree on Israel’s Zionist identity as Jewish and Democratic; have experience in tackling external and internal security threats, though they keep “trashing” one the “miserable” choices of the other; and would not rush to evacuate Jewish towns in the disputed territories. With President Trump’s deal in the horizon (that the totality of evidence, statements, leaks and the evident close relationship with Israel and the cold-shoulder one with the Palestinians indicate its content was carefully coordinated with Israel), either side is expected to accept it under certain terms named publicly.

Iran and other geopolitical challenges

Though Netanyahu has turned countering Iran’s nuclear program and regional activity into his trademark topic, Gantz, if prime minister, is not expected to take any different approach; rather, he already voiced support for Israel’s regional strategy over the past year, and his experience as the army’s chief of staff can assist him in identifying improvement spots in the IDF’s preparation to war. However, these efforts are already being lead at the military level by chief of staff Kokhavi, and it is unclear if Gantz would have the same determination as Netanyahu to fight tooth and nail about Iran with world leaders, or rather let them lead these efforts and focus on tackling Iranian presence in Syria, Lebanon and Iraq.

In any event, none of the candidates to prime ministership is expected to deviate Israel to a radically different international policy than the current one – forging covert and overt relations with its Arab neighbors, tackling Iran, keeping an interest-based relationship with Russia and the EU, forging new alliances in Africa and South America, and consolidating the close relationship with the US.

A political stalemate

Therefore, support for a unity government is growing, even by the leaders themselves, in order to put self-interests second and find a way to serve the public as first priority. At this point, however, things are becoming complicated. Upon receiving the President’s mandate, Netanyahu publicly called Gantz to join in his government and offered what he called a “compromise scheme”. En revanche, Blue and White are demanding Netanyahu to step down in return to forming a coalition government with the Likud, and so is Lieberman; the Likud on its part reaffirmed Netanyahu’s position as their only candidate and formed, under his pressure, a unified right-wing block at the negotiating table with their other potential partners. Netanyahu even repeatedly made his party members and other heads of parties sign documents reaffirming that in writing, in what his rivals sarcastically dubbed an “oath of loyalty”.

Now, Gantz is facing a dead end having been assigned to form a government second, with the option of either forming a short-living minority government or lean on the outside support of the infamous Joint Arab List: unprecedently in Israel’s history, an Arab party, with the exception of one faction, recommended a prime ministership candidate – Gantz – to the President. It is not their ethnicity (their MPs include few Jewish representatives) but their overt Anti-Zionism and support – blunt or in silence – to an armed struggle that makes them particularly controversial.

Hence, neither party would renounce its core demands, nor can either of them form a government alone. Personal exclusions between all parties are numerous. One of the solutions is a rotation government between Netanyahu and Gantz, a recipe already tried in the 1980s; but this faces ample political difficulties. With all sides taking a “my way or the high way” attitude, the President, responsible to give a Knesset member the authority to form a government, is now in the center of a tough dilemma. Israeli citizens, eager to see stability, are meanwhile those slipping through the cracks.

The author Or Yissachar, an Israeli citizen, is AIES intern and expert on international security