The Israeli military occupation of the Palestinian territory imposes a huge price on the Palestinian economy. Israeli restrictions, in fact, prevent Palestinians from accessing much of their land and from exploiting most of their natural resources; they isolate the Palestinians from global markets, and fragment their territory into small, badly connected, “cantons”.

As highlighted also by international economic organisations, including the World Bank, UNCTAD and the IMF, these restrictions are the main impediment to any prospects of a sustainable Palestinian economy.

Many of these restrictions have been in place since the start of the occupation in 1967, reflecting an unchanged colonial attitude of Israel, which aims to exploit Palestinian natural resources (including land, water and mining resources) for its own economic benefits.

This attitude is summed up by Yitzhak Rabin, while holding the post of Israel’s Defense Minister in 1986: “there will be no development initiated by the Israeli Government, and no permits will be given for expanding agriculture or industry, which may compete with the State of Israel” (UNCTAD 1986).

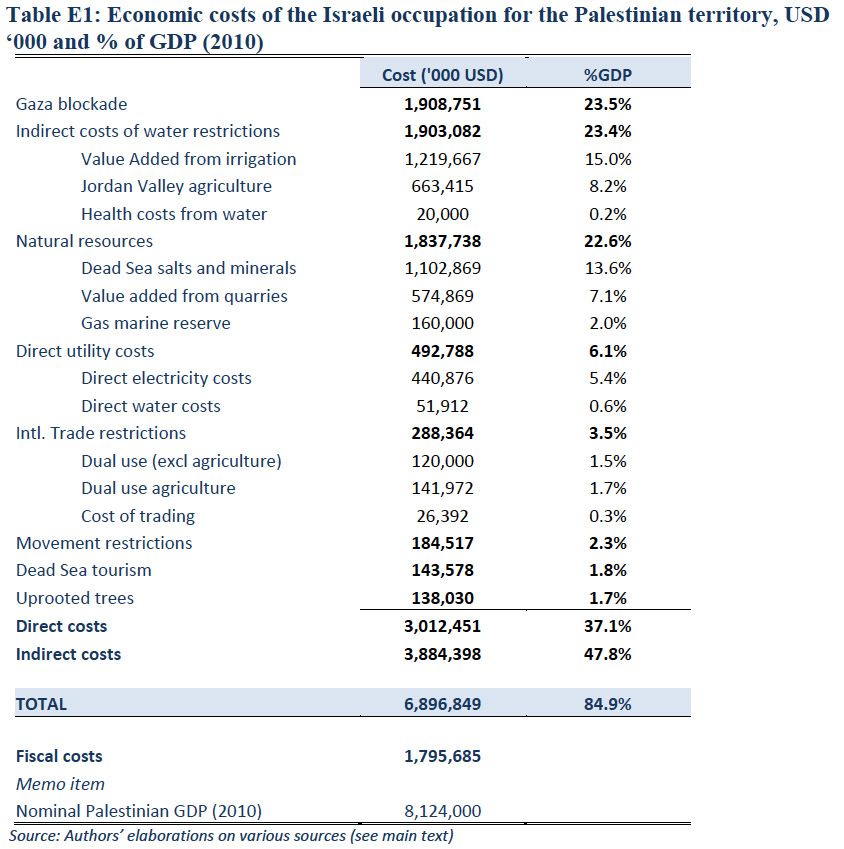

The total costs imposed by the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian economy was USD 6.897 billion in 2010, a staggering 84.9% of the total estimated Palestinian GDP. In other words, had the Palestinians not been subject to the Israeli occupation, their economy would have been almost double in size than it is today.

Costs of exports and imports

Israel imposes a variety of restrictions on the trade to and from the West Bank and Gaza, including with Israel. These restrictions lead to different types of costs, which we divide into two categories:

- Lack of availability and higher costs of inputs to production due to the ‘dual use’ item list.

- Costs of the restrictions in handling, processing and transporting imports and exports.

‘Dual-use’ items are goods, raw materials and equipments and spare parts that have both civilian use as well as potentially other harmful use to which they could be diverted after import into the West Bank and Gaza.

To control imports by Palestinian businesses, the Israeli Government has established a system of bureaucratic controls that require. The system requires the importers to obtain a license in order to import the dual use items; however, most companies fail to get the license. The authorization is obtained through an application process for permits and licenses, but the authorization for many goods is so rarely obtained that, in effect, the goods are banned.

As described above, Israel also imposes particularly burdensome procedures on Palestinian imports and exports mostly in the name of security.

The difference measured by the World Bank (2010) is considerable with Palestinian imports and exports being subject to twice the costs of Israeli imports and exports. The time difference is even more significant, with importing procedures taking on average as much as four times longer for Palestinians than for Israelis (40 days vs. 10 days).

As both Israeli and Palestinian businesses use the same port facilities in Israel, the difference in cost should be entirely attributable to the extra restrictions imposed only on Palestinian goods, with the exception of “inland transportation and handling”.

Restrictions on the use of water resources

Palestinians have had very limited access to the water resources within their territory in the post-1967 border as Israel has taken control of most of them, including the water from the Jordan river and from the underground aquifers.

For example Palestinians only have access to about 10% of the annual recharge capacity of the West Bank’s water system.

If enough water were available to the Palestinians, as according to an equitable distribution of the water resources based on principles of geographic location and fairness, and if the restrictions in Area C were lifted, the Palestinian agricultural sector could drastically expand its production. This would occur mainly by irrigating all the suitable agricultural land and by developing high value-added agricultural products in the Jordan Valley. The potential additional value of production derived from such expansion would be considerable.

Uprooted trees

The Urbanization Monitoring department at the Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem estimates that about 2.5 million trees have been uprooted since 1967. The Israeli policy of uprooting trees has been executed for a number of reasons, including the construction of Israeli settlements, the construction of the separation wall, and settlements infrastructure; all of which exclusively benefits the settler population.

Besides representing an irreparable loss to an inherent part of the Palestinians’ land, Israel’s policy of tree uprooting also creates a grave economic damage for the Palestinian people. The vast majority of the uprooted trees have been fruit bearing trees in their highly productive period of life; thus the uprooting has deprived Palestinians of a valuable source of income.

The olive harvest is a “key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians,” stated OCHA’s 2012 report on the annual harvest published Tuesday 16 October. The report reiterated Israel’s obligation to protect Palestinians and their property while ensuring accountability when attacks by settlers occur. In an overwhelming majority of cases, Israel has done neither.

OCHA estimates that there are 12 million olive trees in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt), mostly in the West Bank. In total, the olive oil industry makes up 14% of the agricultural income for the oPt (1.4% of GDP) and supports the livelihoods of approximately 80,000 families. One third of all Palestinian women working are employed in the agricultural sector.

Electricity restrictions

The main constraints facing the development of the Palestinian energy sector are restrictions imposed by Israeli policies and actions. These constraints arise from: (i) Israeli control over parts of the West Bank (Area C) which can impose a serious challenge to constructing the power network in these areas in the event that Israeli cooperation and coordination is not forthcoming; (ii) Israeli control of Palestinian territorial borders, particularly in the West Bank, which can effectively deny or limit trade across international borders, including importation of electricity and petroleum products through physical interconnections; (iii) Israeli destruction of Palestinian power system facilities by military action, such as the June 2006 attack on the Gaza Power Plant that created a serious short-term crisis for power users in Gaza; (iv) Israeli related impediments to the Gaza marine gas field exploitation.

Obstacles to domestic movement of goods and labour

The movement of goods and people within the West Bank has been heavily restricted by Israel for over a decade through a system of check-points, road-blocks and other barriers. The restrictions slow down vehicle traffic and often force traffic to take the least direct route to a particular location, such as in the case of the Bethlehem-Ramallah route, which cannot go through East Jerusalem. These barriers have been officially established by Israelis for security reasons. This system, however is maintained by Israel regardless of the level of violence in the oPt, has sadly become a permanent landmark of the Israeli occupation. These Israeli restrictions are among the most critical constraints on competitiveness, international investment, and economic development in the West Bank. They result in huge transfer delays and higher transaction costs that affect the productivity of the public and private sector alike.

Last updates

In a report issued on Tuesday March 19 ahead of a meeting of global donors in Brussels, the World Bank explored the long-term damage to the economy as a result of the worsening financial crisis facing the Ramallah-based government and the absence of peace talks, which have been stalled since late September 2010.

“While urgent attention to the short-term financing shortfalls is essential, it is important to recognize that the continued existence of a system of closures and restrictions is creating lasting damage to economic competitiveness in the Palestinian Territories,” the report said.

“The longer the current, restrictive situation persists, the more costly and time-consuming it will be to restore the productive capacity of the Palestinian economy,” it concluded.

Verwendete Literatur

- IMF (2011) Macroeconomic and fiscal framework for the West Bank and Gaza: Seventh review of progress

- Palestinian Ministry of National Economy (2010), Minutes of meeting of the Private sector development and trade sector working group, Ramallah, September.

- UN OCHA (2011), West Bank Movement and Access Update, Jerusalem.

- UNCTAD (1986), Recent economic developments in the occupied Palestinian territories, UNCTAD/TD/B/1102.

- UNCTAD (2011) Report on UNCTAD assistance to the Palestinian people: Developments in the economy of the occupied Palestinian territory , UNCTAD: Geneva.

- World Bank (2009), Assessment of Restrictions on Palestinian Water Sector Development, Sector Note.

- World Bank (2010), The Underpinnings of the Future Palestinian State: Sustainable Growth and Institutions, Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committeee.

- Ysh Din (2009), Petition for an Order Nisi and an Interim Injunction, The Supreme Court of Israel, Jerusalem.